Breeding the Old Maiden Mare

By Dr. Jonathan F Pycock, B.Vet.Med., Ph.D., D.E.S.M., M.R.C.V.S.

Equine Reproductive Services, Messenger Farm, Ryton, Yorkshire

Breeding OR inseminating a mare induces an immediate inflammatory response in the uterus. This is a physiological reaction against foreign material. In most mares this inflammation clears within 1 or 2 days. Mares susceptible to mating-induced endometritis are known to accumulate fluid in the uterus as a result of impaired clearance of inflammatory products. Reduced myometrial contractions, poor lymphatic drainage, a large, overstretched uterus and cervical incompetence are predisposing factors for persistent-mating induced endometrititis.

It is particularly important to recognise and manage appropriately the older maiden mare as in many cases these mares are susceptible to post-breeding endometritis even though they have never been bred before. Often sport or Warmblood mares may not be presented to be bred until they are in their teens and these older maiden mares can be very difficult to get in foal. Many of these mares have some common characteristics which resemble a syndrome. Endometrial biopsy samples reveal glandular degenerative changes and stromal fibrosis (endometrosis) as an inevitable consequence of ageing despite the fact they have not been bred (Ricketts and Alonso 1991).

Another of the most common characteristics of these mares is uterine fluid. Often an older maiden mare has an abnormally tight cervix which fails to relax properly during estrus so that fluid is unable to drain and accumulates in the uterine lumen (Pycock 1993). In many cases this fluid is negative for bacterial growth and presence of neutrophils. Once the mare is bred the fluid accumulation will be aggravated due to poor lymphatic drainage and impaired myometrial contraction compounded by the tight cervix. The amount of intrauterine fluid will vary in individual mares ranging from a few mls to over a liter in extreme cases.

To maximise the fertility of these mares it is vital that the veterinarian is aware of the possibility of this type of uterine and cervical pathology. All too often owners assume that the fertility of these mares is comparable to that of young maiden mares; one of the most important aspects of breeding the old maiden mare is to make the owner aware that there is a high possibility that she will be a problem.

These mares must be considered highly susceptible and managed accordingly:

A) HYGIENE

- Good hygiene at foaling is essential: mares should be thoroughly examined postpartum for any compromise of the physical barriers to uterine contamination.

- Gynaecological examinations, particularly of the vagina, should be performed as aseptically as possible. Thorough digital examination of the cervix can identify fibrosis, lacerations or adhesions which may need treatment before breeding. Since air in the vagina can cause irritation of the mucosa, it should be expelled by applying downward pressure with the hand through the rectal wall.

- Attention to hygiene at mating by using a tail bandage and washing the mare’s vulva and perineal area with clean water (ideally from a spray nozzle).

B) CORRECT TIMING OF BREEDING

- Breeding should occur at the optimal time and the number of breedings should be restricted to one. This means that these mares need very close monitoring (daily) of the estrous period by rectal palpation and ultrasonography. The use of human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG) is strongly recommended in such mares in an attempt to ensure they are only bred once. Recently, use of a gonadotrophin releasing analog, deslorelin, has been found as effective in inducing ovulation as hCG.

- Prediction of ovulation can also be made easier by not breeding these mares before they have begun to cycle regularly. If feasible, the use of artificial insemination can be helpful to reduce (but not eliminate) the inevitable post-breeding endometritis.

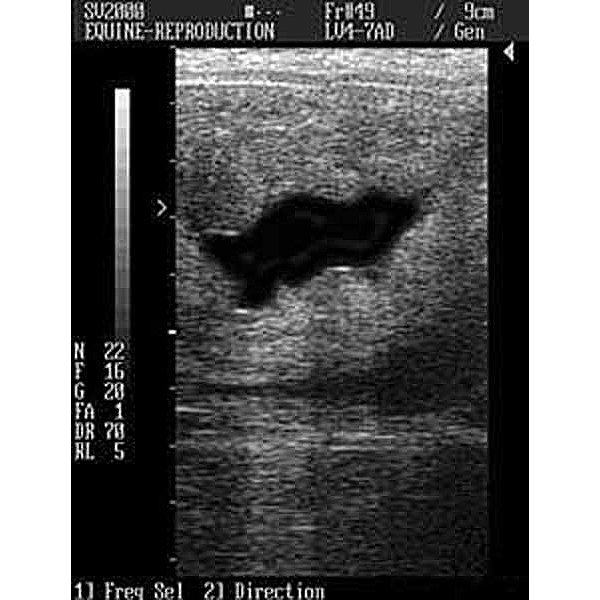

C) ULTRASOUND EVALUATION OF THE UTERUS

Use this for detection of intraluminal uterine fluid before mating. Even if cytology and bacteriology have been negative before breeding, mares susceptible to postbreeding endometritis usually accumulate fluid in the uterine lumen for more than 12 hours after breeding.

D) CORRECTION OF ANY CONFORMATIONAL DEFECTS

Suitable treatment for a mare with such poor reproductive conformation as is shown at left may include Caslick’s procedure or a more involved episioplasty and reconstruction of the vulva; cervical reconstruction; and/or urethral extension.

E) TREATMENT REGIME

Before Breeding: Work has shown that, although initially sterile and free of neutrophils, mares with uterine fluid accumulation before mating have a reduced pregnancy rate when no treatment is performed (Pycock and Newcombe 1996). If more than 0.5 cm fluid is detected, give 25 iu oxytocin as an intravenous bolus. Confirm that the fluid has gone at the next ultrasound examination. If intraluminal fluid is still visible, repeat the dose of oxytocin and, possibly, digitally dilate the cervix also. If more than 2 cm of fluid was present, the uterus was lavaged as described earlier. In general, antibiotics before breeding should be avoided due to possible irritant and/or spermicidal action. [Update 2020: Added to this is the danger of increasing superinfection risk and increasing the possibility of antibiotic resistance. Antibiotic use is now generally limited to targetted treatment of identified pathogenic presence.]

Endometrial cytology smears should be prepared in conjunction with uterine cultures. Presence of inflammatory cells such as neutrophils pre-breeding are indicative of a uterine problem, but some older maiden mares may have uterine fluid present that has no inflammatory cells, and yet is still a significant problem. Post-breeding neutrophils are normally present but are typically cleared within 36 hours in the non-susceptible mare.

A single breeding must be arranged 1 to 2 (or even 3) days before the anticipated time of ovulation. It is my experience that most stallion spermatozoa are viable at least 48-72 hours after mating and this is also supported by Umphenour et al (1993). Records will soon indicate if the semen from a particular stallion is not viable after 48 hours. This early mating allows more time for drainage of fluid via an open oestrous cervix and also utilises the natural resistance of the tract to inflammation during oestrus. It allows sufficient time to flush the mares more than once before ovulation if necessary. Although uterine lavage is possible after ovulation, it is more complicated since the cervix starts closing. Moreover, the resistance of the tract is reduced and the uterotonic effect of oxytocin is reduced due to the increasing amount of circulating progesterone (Gutjahr et al 1998). In the author’s opinion, treatment for endometritis is ideally performed before ovulation. Progesterone concentrations rise rapidly in the mare and any post-ovulation treatment has an increased risk of uterine contamination. In addition, uterine fluid is less likely to drain if the cervix is beginning to close.

After Breeding:

Ultrasound examination of the uterus the following day after mating is performed to assess the amount and echogenicity of any intrauterine fluid. If more than 2.0 cm of fluid was present in the uterine lumen, lavage of the uterus with 1-2 litres of warmed, buffered, sterile saline using a uterine flushing catheter was performed. During lavage, intravenous administration of 25 iu oxytocin was performed. In cases where the cervix has failed to relax adequately, digital dilation of the cervix, with scrupulous attention to cleanliness, is indicated. This is followed by infusion of a low volume (40 ml) of water-soluble, broad-spectrum antibiotics such as already described neomycin sulfate (1 g), polymyxin B (40000 IU), furaltadone (600 mg) (Utrin Wash; Vetoquinol UK) and crystalline benzylpenicillin (5 megaunits) instilled through the cervix into the uterus via a sterile irrigation catheter. I use a low volume of antibiotic solution as, if these mares have a drainage problem, it seems logical to use the minimum effective volume. Older, pluriparous mares may need larger volumes (up to 80 ml). It is my experience that with larger volumes (above 150 ml) some of the solution is lost via cervical reflux. [Update 2020: In the last 17 years since this was first written, increasing knowledge about the possibility of antibiotic resistance has become available. Antibiotic use is now generally limited to targetted treatment of identified pathogenic presence, with rare exceptions.]

Ultrasound examination of the uterus the following day after mating is performed to assess the amount and echogenicity of any intrauterine fluid. If more than 2.0 cm of fluid was present in the uterine lumen, lavage of the uterus with 1-2 litres of warmed, buffered, sterile saline using a uterine flushing catheter was performed. During lavage, intravenous administration of 25 iu oxytocin was performed. In cases where the cervix has failed to relax adequately, digital dilation of the cervix, with scrupulous attention to cleanliness, is indicated. This is followed by infusion of a low volume (40 ml) of water-soluble, broad-spectrum antibiotics such as already described neomycin sulfate (1 g), polymyxin B (40000 IU), furaltadone (600 mg) (Utrin Wash; Vetoquinol UK) and crystalline benzylpenicillin (5 megaunits) instilled through the cervix into the uterus via a sterile irrigation catheter. I use a low volume of antibiotic solution as, if these mares have a drainage problem, it seems logical to use the minimum effective volume. Older, pluriparous mares may need larger volumes (up to 80 ml). It is my experience that with larger volumes (above 150 ml) some of the solution is lost via cervical reflux. [Update 2020: In the last 17 years since this was first written, increasing knowledge about the possibility of antibiotic resistance has become available. Antibiotic use is now generally limited to targetted treatment of identified pathogenic presence, with rare exceptions.]

It is vital that the antibiotic used [if used] does not irritate the endometrium or predispose to overgrowth with fungal organisms. Neither of these problems have been observed using the antibiotic combination described here.

Further doses of 25 iu of oxytocin are given every four to six hours by the stud farm personnel. This is by the intramuscular route. In mares with lymphatic stasis, the slower release of prostaglandin (cloprostenol 500mcg IM) may be useful in addition to oxytocin. The cloprostenol should be given some 6 to 8 hours after the first oxytocin injection [and should not be used more than 12 hours post-ovulation. LeBlanc et. al.]

The mare is re-examined the following day and oxytocin treatment repeated if fluid is still present. Only rarely will a second infusion of antibiotics or lavage procedure be performed due to the risk of uterine contamination. Evaluation of the uterus post-breeding is a crucial time to assess all mares and too many clinicians fail to evaluate mares post-breeding.

An important concept is to treat in relation to breeding and not wait for ovulation!

I had the opportunity to investigate the optimum time of treatment in a study with a Swiss colleague, Barbara Knutti (Knutti et al 2000). In our practice, known susceptible mares are routinely treated the day after breeding. Working on the principle that the longer a foreign particle stays in the uterine lumen, the more neutrophils accumulate, an earlier treatment should reduce the inflammatory reaction and improve the chances for these susceptible mares to get pregnant.

Eighteen barren mares with a mean age of 15 years were selected. They had been barren for more than one year, had been inseminated during >6 oestrous periods, had a history of fluid after breeding and had failed to become pregnant with the standard protocol for management as described above.

Experimental Approach: In nine mares, the standard protocol was repeated (control). In the other nine mares, the standard protocol was performed with the only change that the mare’s uterus was flushed 4-6 hours after insemination.

Results: Twice as many mares with the early lavage were pregnant compared to the group of mares not lavaged until 18-20 hours after insemination.

Mechanical removal of uterine contaminants as soon as possible should be the aim of treatment of persistent mating-induced endometritis (Brinsko et al 1991; Pycock 1994a, b; Troedsson 1997). The beneficial effect of oxytocin is widely accepted (Pycock 1994a, b; Rasch 1996). The combination of both treatment options is effective in clearing even large amounts of intraluminal fluid. The decision to perform uterine lavage only when more than 2 cm of intraluminal fluid was detected was based on the clinical experience that smaller amounts of fluid could usually be cleared from the uterus with oxytocin alone, which is a time-and cost- saving treatment. To be certain that oxytocin injection would not interfere with sperm transport in the uterus and oviduct, the drug was not administered immediately before or after insemination.

The optimal time to perform a large-volume uterine lavage in relation to insemination or mating has not been determined. Uterine contaminants should be removed as soon as possible after mating, while on the other, sperm cells could be detected in the oviduct between 2-4 hours after insemination (Bader 1982). Additionally, uterine lavage performed 4 hours after insemination did not harm the sperm cells or influence pregnancy rate, whereas pregnancy rate was reduced when the lavage was performed 0.5 or 2 hours after insemination (Brinsko et al 1990, 1991). Therefore, the time interval of 4-6 hours was chosen to perform the lavage. The results of this study correlate with the findings of Brinsko et al (1991) that a uterine lavage performed 4 hours after insemination does not adversely affect conception rate.

Conclusion

Some questions remain unanswered: Hearn (1993) voiced the concern that the early embryonic/foetal loss rate of susceptible mares with endometritis who receive aggressive post-mating therapy will be much higher despite the temporary improvement in uterine environment. Undoubtedly the live foal-rate of mares which are extensively treated post-breeding is less than in young, genitally-healthy mares. However, often susceptible mares are old and frequently when uterine biopsy results are available, these often confirm degenerative changes within the endometrium. Consequently one’s live-foal rate expectations are lower in these mares in any case.

In my daily routine, I assume that most multiparous mares are at risk for either clinical or subclinical endometritis following insemination, be it natural or artificial. Routine post-mating treatment of mares believed to be at risk of persistent acute endometritis is dependent on balancing cost and time against benefits to the breeder. This view is also held by Australian colleagues who claim increased pregnancy rates and subsequent foaling rates through routine post-mating treatment (Pascoe, personal communication; Pascoe 1995). The results of published clinical studies (Pascoe 1995; Pycock 1994 a,b; Pycock 1996) and many breeding seasons field experience with large numbers of mares have demonstrated the effectiveness of a single post-mating treatment to combat endometritis. This has certainly been the case in the mares with which I have been involved. Against this improvement in pregnancy rate, it must be examined if there is any reason, not to routinely treat all mares after mating:

Certainly management standards must not fall. Post-mating treatment should not be seen as a means of getting away with poor management.

No bacterial resistance problems or increase in fungal endometritis must be apparent with the intrauterine antibiotics used. At the first International Symposium on Equine Endometritis, Zent (1993) reported that, of 4000 broodmares in his Kentucky veterinary practice, all except maiden mares were routinely given at least one post-mating intrauterine antibiotic infusion. He believed this treatment had improved pregnancy rates, without the development of a resistance problem or an increased incidence of fungal endometritis. [Update 2020: In the last 17 years since this was first written, increasing knowledge about the possibility of antibiotic resistance has become available. Antibiotic use is now generally limited to targetted treatment of identified pathogenic presence, with rare exceptions.]

When the susceptible mare should be bred and when should she be treated and either short cycled or bred at the next natural oestrus must be a matter of clinical experience based on history and findings of clinical and laboratory examinations.

Summary: Breeding the Old Maiden Mare

Breeding OR inseminating a mare induces an immediate inflammatory response in the uterus. In most mares this inflammation clears within 1 or 2 days. Mares susceptible to mating-induced endometritis are known to accumulate fluid in the uterus as a result of impaired clearance of inflammatory products. It is particularly important to recognise and manage appropriately the older maiden mare as in many cases these mares are susceptible to post-breeding endometritis even though they have never been bred before. Often sport or Warmblood mares may not be presented to be bred until they are in their teens and these older maiden mares can be very difficult to get in foal. Often an older maiden mare has an abnormally tight cervix which fails to relax properly during estrus so that fluid is unable to drain and accumulates in the uterine lumen (Pycock 1993). In many cases this fluid is negative for bacterial growth and presence of neutrophils. Once the mare is bred the fluid accumulation will be aggravated due to poor lymphatic drainage and impaired myometrial contraction compounded by the tight cervix. The amount of intrauterine fluid will vary in individual mares ranging from a few mls to over a liter in extreme cases.

To maximise the fertility of these mares they must be considered highly susceptible and managed accordingly: Good hygiene is essential; breeding should occur at the optimal time and the number of breedings should be restricted to one; ultrasound should be used for detection of intraluminal uterine fluid before mating; any conformational defects should be corrected

A single breeding must be arranged 1 to 2 (or even 3) days before the anticipated time of ovulation. It is my experience that most stallion spermatozoa are viable at least 48-72 hours after mating and this is also supported by Umphenour et al (1993). Records will soon indicate if the semen from a particular stallion is not viable after 48 hours. This early mating allows more time for drainage of fluid via an open oestrous cervix and also utilises the natural resistance of the tract to inflammation during oestrus. It allows sufficient time to flush the mares more than once before ovulation if necessary. Although uterine lavage is possible after ovulation, it is more complicated since the cervix starts closing. Moreover, the resistance of the tract is reduced and the uterotonic effect of oxytocin is reduced due to the increasing amount of circulating progesterone (Gutjahr et al 1998). In the author’s opinion, treatment for endometritis is ideally performed before ovulation. Progesterone concentrations rise rapidly in the mare and any post-ovulation treatment has an increased risk of uterine contamination. In addition, uterine fluid is less likely to drain if the cervix is beginning to close.

A problem mare, once inseminated or mated should not only be checked for ovulation but also for fluid accumulation in the uterus, one of the most reliable clinical signs of susceptibility to postbreeding endometritis. If a mare is recognised as being susceptible to persistent mating-induced endometritis, intensive postbreeding monitoring and eventually, treatment is necessary in order to improve the chances of conception. The early postbreeding lavage supported by oxytocin and the infusion of broad-spectrum antibiotics have proved to be an effective management for mares susceptible to mating-induced endometritis. [Update 2020: In the last 17 years since this was first written, increasing knowledge about the possibility of antibiotic resistance has become available. Antibiotic use is now generally limited to targetted treatment of identified pathogenic presence, with rare exceptions.]

References

- Bader H : An investigation of sperm migration into the oviducts of the mare. J Reprod Fert Suppl 32, 59, 1982

- Brinsko SP Varner DD and Blanchard TL: The effect of uterine lavage performed four hours postinsemination on pregnancy rates in mares. Theriogenol 35, 1111, 1991

- Brinsko SP Varner DD Blanchard TL and Meyers SA: The effect of postbreeding uterine lavage on pregnancy rates in mares. Theriogenology 33, 465, 1990

- Gutjahr S Paccamonti D Pycock JF van der Weijden GC and Taverne MAM: Intrauterine pressure changes in response to oxytocin application in mares. Reprod dom. Anim, Suppl 5, 118, 1998

- Hearn P: The relationship of uterine inflammation to fertility. Proc Soc Theriogenology: 139, 1993

- Knutti B Pycock JF van der Weijden GC and Kupfer U: The influence of early postbreeding uterine lavage on pregnancy rates in mares with intrauterine fluid accumulations after breeding.

- Pascoe DR: Effect of adding autologous plasma to an intrauterine antibiotic therapy after breeding on pregnancy rates in mares. Biol Reprod Mono 1: 137, 1995

- Pycock JF: A new approach to treatment of endometritis.Equine vet.Educ 6:36, 1994a

- Pycock JF: Assessment of oxytocin and intrauterine antibiotics on intrauterine fluid and pregnancy rates in the mare. 40th Ann Conv Am Ass equine Pract: 19, 1994b

- Pycock JF and Newcombe JR: Assessment of the effect of three treatments to remove intrauterine fluid on pregnancy rate in the mare. Vet Rec 138: 320, 1996

- Rasch K Schoon HA Sieme et al: Histomorphological endometrial status and influence of oxytocin on the uterine drainage and pregnancy rate in mares. Equine Vet J 28: 455, 1996

- Troedsson MHT: Therapeutic considerations for mating-induced endometritis. Pferdeheilkunde 13, 516, 1997.

- Umphenour NW Sprinkle TA and Murphy HQ: Natural service. In McKinnon AO, Voss JL (eds): Equine Reproduction. Philadelphia, Lea & Febiger, 1993, pp 798-808

- Zent W : Post-ovulation intrauterine antibiotics. Proceedings of JP Hughes International Workshop on Equine Endometritis, summarised by WR Allen. Equine vet J 25, 192, 1993

© 2003, 2020 Dr. Jonathan F Pycock, B.Vet.Med., Ph.D., D.E.S.M., M.R.C.V.S.

Presented here with the authors permission.